Everyone knows the story of the Frog Prince. In the famous fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, a spiteful witch casts a spell upon a prince in which the handsome nobleman is turned into an ugly frog. In popular versions, the spell can only be broken by the unlikely event that a princess will overcome revulsion and kiss his slimy frog lips. Cold-blooded indeed, however it´s just a fairy tale; nothing like that could ever happen in reality, right? Well think again, because something similar has happened in La Plata, the capital city of the province of Buenos Aires. Please allow me to explain:

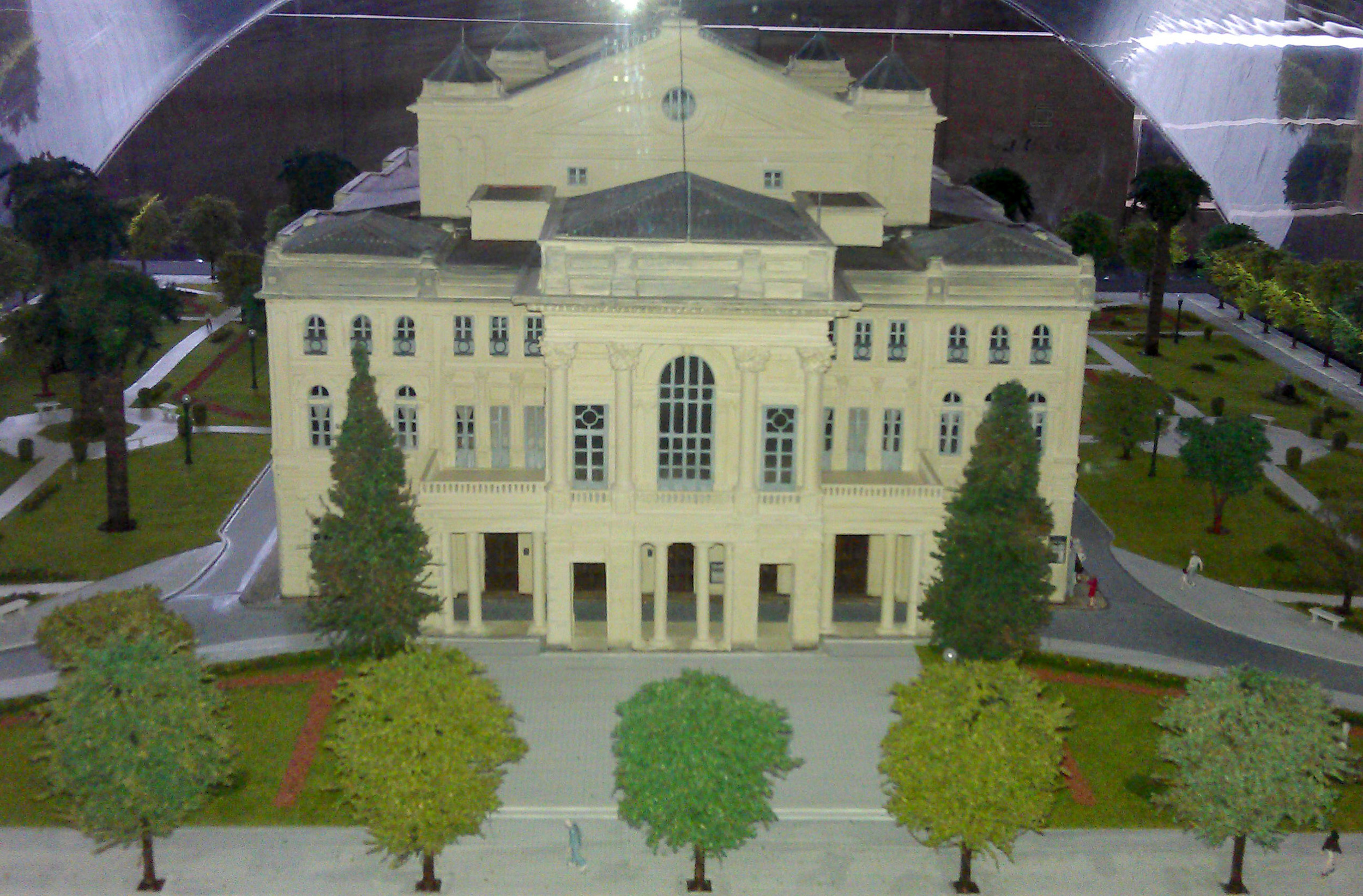

Once upon a time, there was a handsome

opera house, known as Teatro Argentino. It was designed by Italian architect Leopoldo Rocchi and it was located at avenues 51 and 53, in the heart of the city, among a row of splendid buildings known as the foundational axis of architecture. It was the jewel of La Plata. Completed in 1890, it was built in the classic renaissance tradition and satisfied the most fastidious standards of Italian design. La Plata's opera house was the second grand theater for Argentina. Although slightly smaller, it was comparable to the country´s first opera house, Teatro Colón, which is considered one of the finest theaters in the world. But then, one fateful day, an evil spirit put a curse on Teatro Argentino and it was turned into an ugly monster.

In reality, the calamity that befell the theater was a fire. The incident, which occurred in 1977, gutted the interior of the opera house, and a decision was made to demolish the rest. Then, in a curious move to garner a design for the new opera house, the government decided to conduct a competition. Dozens of designs were submitted and put on display, but the prize went to designers, Henry Bars, Tomas Garcia, Roberto Germani, Ines Rubin, Carlos Alberto Sbarra and Ucar. They were affiliated with a local design college and spawned the beast that now sits at streets, 9 and 10 between 51 and 53.

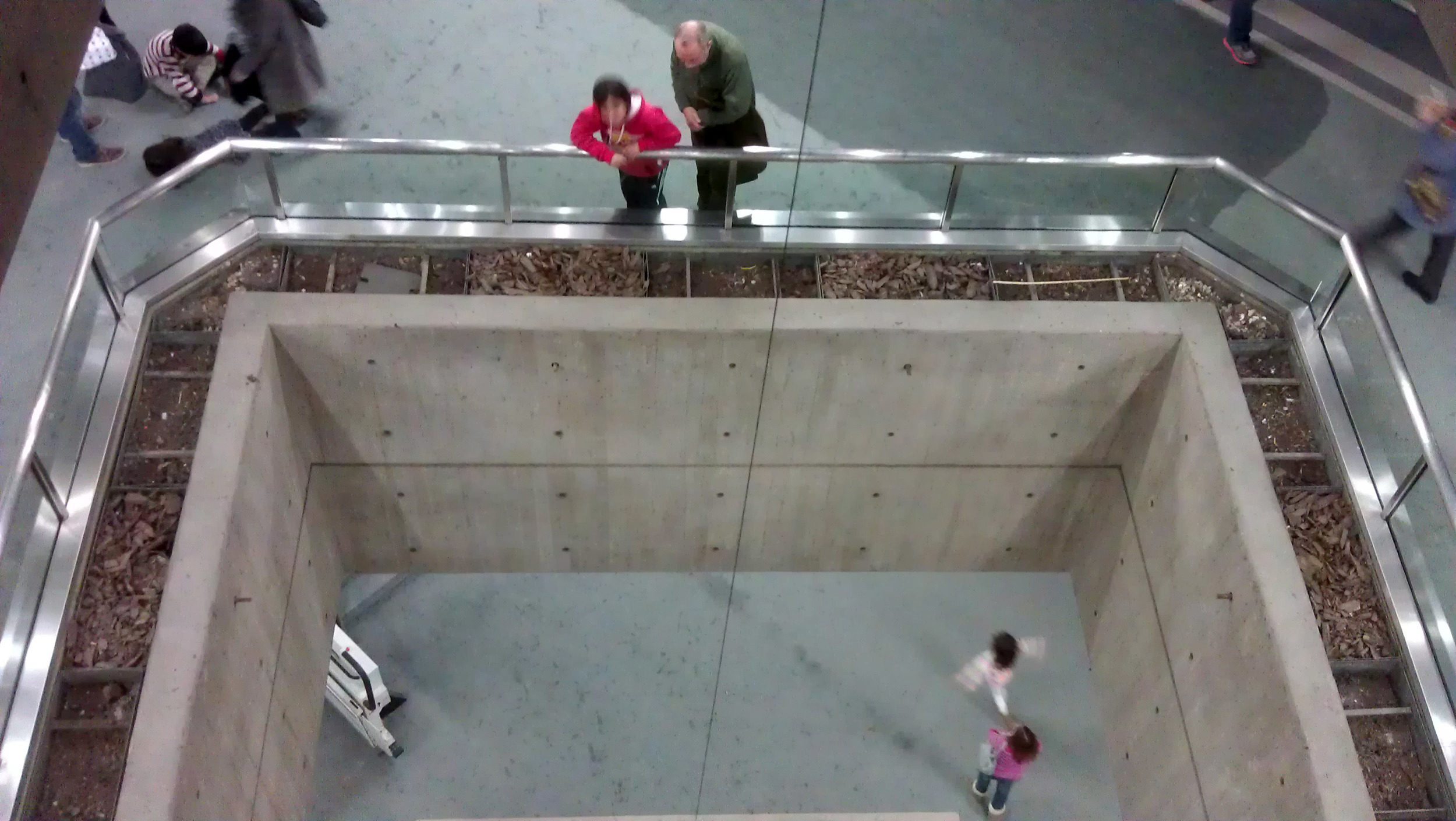

Only by standing in front of Teatro Argentino, is it possible to grasp the shock and awe that it can inspire. It is an enormous concrete bulwark that fractures the neighborhood and defiles the city´s axis of architecture. From street level, it´s possible to peer down several stories into the earth and see the courtyards that surround the foundation of the structure. A thick, metal railing protects the passerby from accidentally falling into the pit. Whatever adornments there were in that place are gone, and it looks like an empty well. From the bottom, the eye can travel up the precipitous exterior to a breath-taking height where it is suddenly truncated by ruthless angles in the roof, angles that purport to echo the diagonals in Pedro Benoit´s urban plan of La Plata. Black, tinted windows and exposed ironwork add a disturbingly sinister mood to the behemoth. Yes, just like the frog in the fairy tale, Teatro Argentino is difficult to cuddle-up with.

Though Teatro Argentino feels much larger than Teatro Colón, its hulking appearance is deceptive. Its main theater, Alberto Ginastera, has a maximum capacity of 2000 spectators, but the Colón can hold nearly 3000. Of course Teatro Argentino is more than just an opera house. It has an art gallery, called Emilio Pettoruti, and another small theater space called Astor Piazolla. However, with its additional offerings the total space of the facility, at 60,000 sq m, is only slightly more than Teatro Colón’s 58,000 sq m space. It feels much more massive because of the architectural style, a phenomenon known as Brutalism.

During the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s, Brutalism was popular everywhere. At the time, it was the most recent manifestation of Modern and was rigorous in its adherence to the mantra, form follows function. One obvious result of that philosophy was a decline in architectural ornament. Expanding upon the Machine Age with grim, German Expressionistic ideologies, Brutalism represented the future for the post-war generation. And it was cheap! Buildings erected in the style were typically made of concrete, or other materials that were economical and readily available. The materials were then left exposed, or raw, a condition summarized by Le Corbusier, as béton brut. Brutalism was especially popular with universities and cultural centers, but the style became popular with government buildings as well. This, perhaps, led to the style being associated with state authority and population control. This, and the fact that, the structures are intimidating, menacing, and irreparably ugly.

It turns out that raw concrete doesn’t age well. It grays and stains, and in some areas, it seems to bleed rust. It is also irresistible to the graffiti artist and the skate boarder. Thus, Brutalist architecture grows uglier with time and becomes symbolic of urban decay. Given its context, Teatro Argentino is even more shocking. Surrounded by sumptuous Renaissance, Baroque and Gothic architecture, it is the avatar of Brutalist style. It also suffers all the vexation that accompanies the style.

The interior of Teatro Argentino is as austere as the exterior. It’s cavernous and dusky and the thin carpet stretched over the hard surfaces provides little respite from the cold minimalism. Near the concessions, a crumbling relief sculpture in the wall draws the eye, but the tormented figures depicted there only add to the air of unease generated by Teatro Argentino. Each floor has a cavity in the middle, which opens the space and emulates the shear drops to the courtyards found outside the building. From the lobby of Teatro Argentino, it’s hard to imagine that the building could provide the quality of sound demanded by a world class opera house, but that notion is soon eliminated by Alberto Ginastera.

The main theater, Alberto Ginastera, is the nucleus of Teatro Argentino, and it is strikingly different from its outer shell. Its red corduroy interior re-creates the classic Italian horseshoe shape and the harmonic ratio associated with exquisite acoustics. The space features four levels of boxes and galleries and a colossal, three ton, bronze chandelier, a replica of the one in the original theater, hanging from the ceiling. The theater doesn’t have all the ornament of the Colón, but its sound, lighting, and stage technologies emulate Teatro Alla Scala, in Milan, and place Teatro Argentino among the world’s great theaters, at least in terms of utility. However, in terms of aesthetics the poor theater remains under the witch’s curse. It desperately needs the kiss of a princess to break the spell, but how might that manifest?

A recent article, published by CityLab/The Atlantic, predicts that the J Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, DC, a Brutalist style building, will soon be torn down. In fact, the article, naming similar buildings facing the wrecking ball, implies that Brutalism could be entirely expunged from cityscapes across the globe. Other articles, like this one from the New York Times, further indicate that, for Brutalism, the end is nigh. Most people abhor the buildings and want them torn down. In the interview with The Times, experts cite the costs of updating and maintaining these “monuments to inefficiency” as opposed to the cost of demolition. Yes, it appears that many of these buildings are doomed and that might be a good thing for Teatro Argentino.

The aesthetic experience is not limited to beauty. Appreciation can derive from knowledge. Clearly, Brutalism makes a powerful impact, and how the individual interprets the experience will naturally vary. However, if the majority of brutalist architecture is destroyed, then Teatro Argentino becomes even more unique and special. It may, one day, stand alone as the representative of a bold vision of the future. It could be a rare example of a historical moment that will always stimulate discourse. Perhaps, due to the inevitable scarcity of Brutalist structures, Teatro Argentino will become more precious, more symbolic and could it be- more beautiful. Indeed, to break the witch’s spell, Teatro Argentino only needs to wait. With time, and with understanding, people’s perspective may change and the frog will get his kiss.