In the gothic masterwork, Melmoth the Wanderer, in the section called The Lovers’ Tale, Charles Maturin describes a powerful landowner called Mortimer. This ancient family dwelled in a grand castle that towered over their domain, the fertile fields of Shropshire, England. Maturin describes the castle’s inmates as indulging in an aristocracy of imagination, that is to say they were all, without exception, wholly ensconced with the tenets of the Church of England and the House of stuart.

The art that hung on their walls, the literature that composed their library, and the raconteurs that delighted their youth, all reinforced and validated their religious and political views. For the Mortimers, any opposing perspectives amounted to blasphemy and warranted abolition, and of course they possessed the means to do thus.

Therefore there prevailed, in the kingdom, no opposing views and many were ignorant that there could exist such things at all. Yes, Maturin was as accurate as he was poetic when he characterized the Mortimers as an aristocracy of imagination, and perhaps even more instructive when he stated that it was an indulgence.

The reader might detect contemporary parallels. Consider how, in today’s “United” States, people surround themselves with those who support their own views, consume media designed to validate those views, and banish or attack those who present opposing perspectives. Indeed, in America today, people construct their domains just like the Mortimers, and even if they don’t possess castles so that they can literally wall themselves off, they are still, like the Mortimers, incapable of identifying an element of common ground in their opposing party. In the words of Maturin, an ancient geographer would have been just as likely to have pointed to America on a classical map as the Mortimers would have been to find a modicum of goodness in their antagonist.

In the art world, as narratives have shifted, similar phenomena are observable. Anthony Julius, writing in a recent article for Liberties Journal entitled, “Art’s Troubles”, stated that “new terms of engagement have been established, across political and ideological lines, in receptions of works of art.” Every party, be they the state, ecclesiastics, the left, the right, or even artists themselves, has their own perspective, and examples abound of art being condemned by respective parties for reasons ranging from cultural appropriation to hate speech to sexism.

Today, artists such as Gauguin are exhibited with disclaimers, and Picasso’s legacy as a pioneer of modern art has been recontextualised as an example of misogyny and toxic masculinity. One might examine the works of Balthus or Courbet or countless other white, male artists, for whom it might be said, are leveraging their privilege and power to exploit female identities in order to satisfy their own and other white male’s fantasies. And while there is, no doubt, evidence to support this perspective, this artist, speaking as a male in a climate of censorship and intolerance, would like to invite the reader to consider the following perspective, one that emphasizes the significance of the art nude.

It’s important to acknowledge, as British art historian, Kenneth Clark, has said, that nude is not the same as naked. Naked implies vulnerability and shame while nude suggests harmony, certitude, and even majesty, especially in the context of art and judgements of tastes. Naked is of little use to artists while, ever since the 5th century when the Greeks invented it, the art nude is aspired to by artists as a concept. The nude is not the subject of art but itself a form of art. In practice, the artist takes the frail and corruptible flesh of the human body and transforms it into something pure and unassailable. Aristotle has famously stated, “Art completes what nature cannot bring to a finish.”

For this artist, as with most artists who are classically trained, the nude represented the core of academic discipline. At the Savannah College of Art and Design the nude was the benchmark of the student’s ability. It was said that the nude was the ultimate expression of form and it follows that many objects encountered and interacted with, from the Coca-cola bottle to Calatrava’s Swedish skyscraper, the Turning Torso, are directly informed by or at least reflect that concept. Clark, in his work The Nude: A Study In Ideal Form, declares that the nude does not simply represent the body, but relates it by analogy, to all structures that have become part of our imaginative experience.

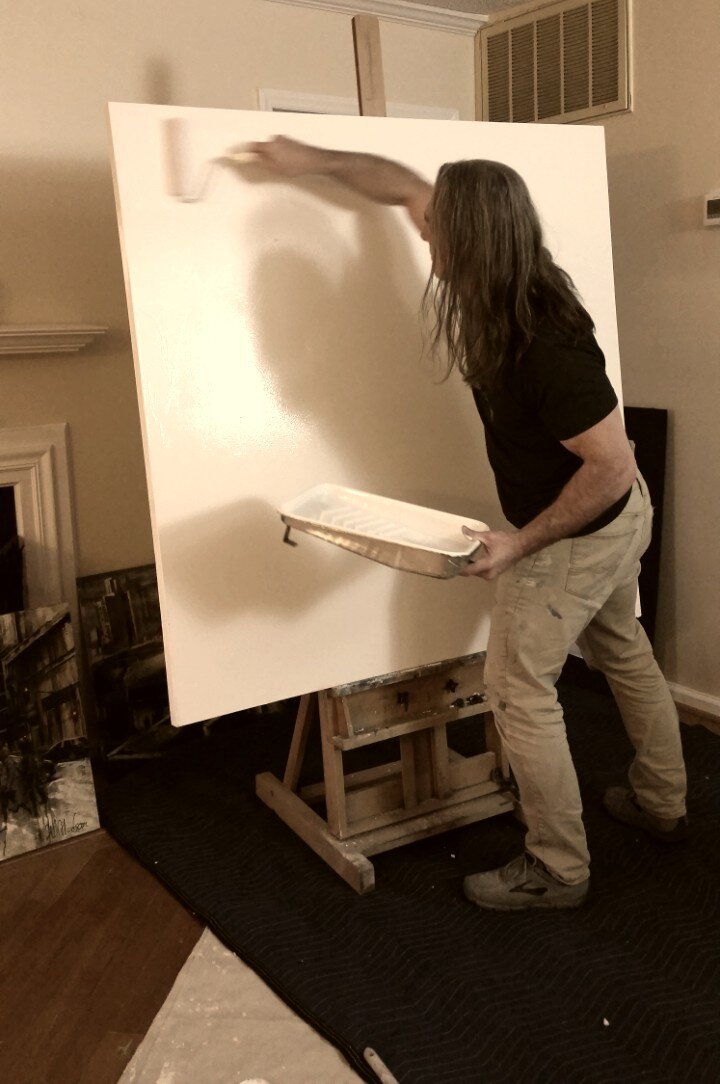

This oil painting, Aristocracy of Imagination, is an art nude in the western tradition. That is to say, it celebrates an ideal. It seeks to awaken pathos. And above all, it seeks to re-introduce beauty into the contemporary art conversation.

Its title comes from Maturin’s novel and is so called in an attempt to challenge the viewer to surrender the indulgence of a singular perspective. It’s the artist’s hope that the viewer will engage with the artwork and find within it the harmony, the energy, and the ecstasy that composes the human experience.

I hope you enjoy Aristocracy of Imagination.